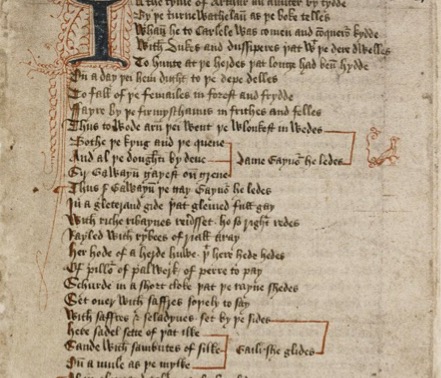

In his Anglica Historia (1534), Polydore Vergil published his scathing comments about Geoffrey of Monmouth, which subsequently ignited a debate over the veracity of the Historia regum Britanniae.[1] Quoting the twelfth-century historian, William of Newburgh, he writes that

there hathe appeared a writer in owre time which, to purse these defaultes of Brittains, feininge of them thinges to be laughed at, hathe extolled them above the nobleness of Romains and Macedonians, enhauncinge them with moste impudent lyeing. This man is cauled Geffray, surnamed Arthure, bie cause that oute of the olde lesings of Brittons, being somewhat augmented bie him, he hathe recited manie things of this King Arthure, taking unto him both the coloure of Latin speech and the honest pretext of an Historie.[2]

Vergil believed the Historia to be largely fictitious: he regarded Brutus to be an invention of the author, and he also suggested that Geoffrey’s portrait of Arthur had been highly embellished. British historians and antiquarians, such as John Leland, John Prise, and Humphrey Llwyd, were not receptive to the Anglica Historia, and they rushed to defend Geoffrey.

Yet Polydore Vergil’s objections about the Historia regum Britanniae were not new. In the twelfth century, Gerald of Wales and – most famously – William of Newburgh had their doubts about the reliability of Geoffrey’s work. Vergil, then, was merely continuing a tradition of skepticism about the Historia that had been popular since the twelfth century, and so his comments were not, necessarily, the product of Renaissance humanist doubt. This short post will consider how medieval and early modern commentators on the Historia regum Britanniae used their scholarly arguments to explore ideas of authority and authorship; in particular, it focuses on how William of Newburgh and John Leland used their evaluative historiographical practices to influence the reputation of Geoffrey of Monmouth.

William of Newburgh

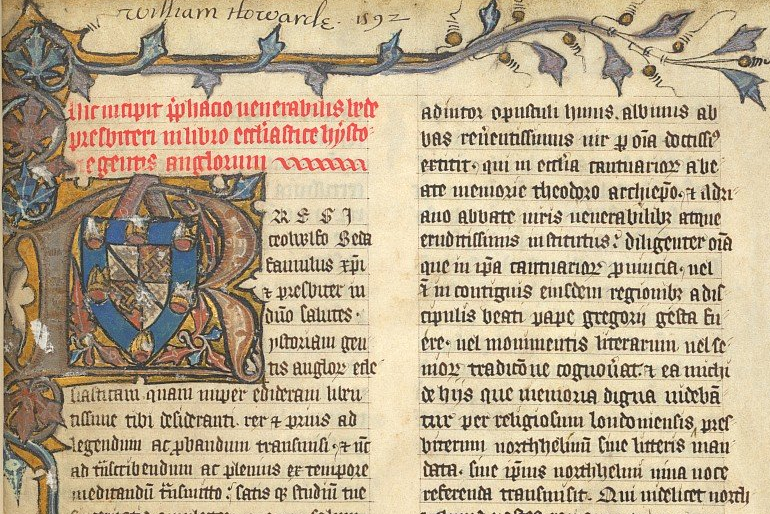

Geoffrey’s most profound early critic was William of Newburgh. His skepticism of the Historia regum Britanniane is well documented in his Historia rerum Anglicarum (‘The History of English Affairs’, c. 1198), a history of the Anglo-Norman kings from William I to Richard I, which focuses in particular on the civil unrest in the reign of King Stephen. In this text, William includes a vicious attack on Geoffrey and the Historia, and the prologue to his text begins with a treatise on history and truth. He upholds Gildas and Bede as the most esteemed writers of ‘British’ history, particularly as they were committed to revealing the truth about the Britons, but he laments that

in our own day a writer [scriptor] of the opposite tendency has emerged. To atone for these faults of the Britons he weaves a laughable [ridicula] web of fiction [figmenta] about them, with shameless vainglory extolling them far above the virtue of the Macedonians and the Romans. This man is called Geoffrey and bears the soubriquet Arthur, because he has taken up the stories about Arthur from the old fictitious [figmentis] accounts of the Britons, has added to them himself, and by embellishing them in the Latin tongue he has cloaked them with the honourable title of history.[3]

In this passage, William’s main objection to the Historia is its basis in fiction [figemnta], rather than fact, and he complains that such an unreliable work has been produced in Latin, the language of authority. The contrast between fact and fiction demonstrates the unreliability of Geoffrey’s work, especially since the deeds of Arthur in the Historia have been over exaggerated. William insists that here is no justification for such ‘wanton and shameless lying’ (I.5), and dismisses Geoffrey as a mediocre historian who has ‘not learned the truth about events’ (I.5).

William’s prologue continues with a brief descriptive of the Saxon invasion by Hengist, and he lists the English kings that ruled after him, including Ethelbert, Aethelfrith, Edwin, and Oswald. According to William, these are historically accurate [historicam veritatem] events as they are accounted for in Bede’s Historia Ecclesiastica. William then uses Bede’s account to disprove Geoffrey’s version of events, and he claims that

it is clear that Geoffrey’s entire narration about Arthur, his successors, and his predecessors after Vortigern, was invented partly by himself and partly by others. The motive was either an uncontrolled passion for lying, or secondly a desire to please the Britons, most of whom are considered to be so barbaric that they are said to be still awaiting the future coming of Arthur being unwitting to entertain the fact of his death. (I.9)

William’s juxtaposition of these accounts is clearly designed to assert the authority of Bede, rather than Geoffrey. Nevertheless, his assertion that created the Historia ‘partly by himself’, suggests that William also regarded Geoffrey as an auctor who was distinguished from scriptors, compilators, and commentators by their ability to invent their own work.[4] Technically, of course, Geoffrey only fulfills the category of scriptor as he only presents himself as a translator of the ‘British book’, which he claims was given to him by Walter, Archdeacon of Oxford. By acknowledging that some of the content of the Historia regum Britanniae was unique – even it was unaccounted for – Geoffrey’s principal critic is also his most important bestower of auctoritas.

After comparing Geoffrey with Bede, William casts his final judgment over the veracity of the Historia. He interrogates Geoffrey’s account of Arthur’s reign, particularly his foreign conquests, and he remarks

how could the historians of old, who took immense pains to omit from their writings nothing worthy of mention, and who are known to have recorded even modest events, have passed over in silence this man beyond compare and his achievements so notably beyond measure? How, I ask, have they suppressed in silence one more notable than Alexander the Great – this Arthur, monarch of the Britons, and his deeds – or Merlin, prophet of the Britons, one equal to Isaiah, and his utterances? […] So since the historians of old have made not even the slightest mention of these persons, clearly all that Geoffrey has published in his writer about Arthur and Merlin has been invented by liars to feed the curiosity of those less wise. (I.14)

Here, William’s process of evaluation is framed through a series of complex rhetorical questions and juxtapositions focusing on Geoffrey and the ‘historians of old’. The rhetorical questions are designed to reinforce the authority of Gildas and Bede (even if they are not directly mentioned by name), and they imply that it would be unreasonable to doubt the reliability of two writers who recorded every detail of events. William entirely discredits Geoffrey’s attempt to fill the lacuna in insular history, and his conclusion that the stories of Arthur and Merlin Historia must be an invention, especially since they cannot be confirmed by any of the ancient historians, appears to be perfectly valid.

John Leland

The critical attitudes to Geoffrey’s Historia regum Britanniae began to change in the sixteenth century. The English antiquarian John Leland objected to Vergil’s claim that the Historia was an unreliable source, and in his De uiris Illustribus (‘Of Famous Men’, first completed 1535-6 and revised 1543-6), Leland offered a defence of Geoffrey, whom he placed alongside various other writers of ‘British’ history, ranging from the first Druids to Robert Widow. The account in De uiris Illustribus can be considered to be the first biography of Geoffrey, who is described as a man who ‘took great pleasure in reading ancient history’ and who ‘also delighted in scholarly intercourse’.[5] Leland situates Geoffrey within the clerical and academic circles of his time, and he is upheld as model of learning and authority. He praises him for his dedication to ‘British’ history as ‘he stands alone in having rescued a great part of Britain’s antiquity [Britannicae antiquitatis] well and truly from destruction through a diligence [diligentia] which is beyond all praise’ (Leland, p. 308-9). Leland presents Geoffrey as a translator, rather than an author, of his own work, and he writes that

he openly declares that he performed the task [officio] only of an interpreter [interpretis]; in other words, he translated a British history, written in the British language, and brought to him by Walter Map, the archdeacon of Oxford, into Latin. (Leland, p. 310-11)

This remark is essentially an apology for the number of inventions that can be found in the Historia, and it is also designed to counteract the comments of Geoffrey’s critics, who credited him with fabricating many of the events in his work. According to Leland, then, Geoffrey had a limited amount of creative agency, and he simply acted as a cultural mediator by transmitting an ancient account of the ‘British’ past to his twelfth century readers.

Leland’s biography of Geoffrey includes a lengthy scholarly attack on Polydore Vergil. Leland complains that the Italian historian

launches a frenzied attack on Geoffrey, in order to undermine Geoffrey’s authority [autoritatem] and to accumulate weight and force as well as credibility [ueritatem] for his own empty inanities. Then, for much of the earlier part of his history, this most impudent fellow is forced to follow the writer whom he has just torn to pieces with so many harsh words. But one should surely forgive this impertinence when there was practically no other authority [autorem] he could have followed. (p. 310-11)

Here, Leland asserts that Vergil is a hypocrite for discrediting Geoffrey, and then using his account to form the basis of the record of insular history in the Anglica Historia. Leland’s comments also imply that ‘English’ history, from the Saxon period through the Normans to the Plantagenet kings, and the current Tudor monarchy, depends upon early ‘British’ history for its authenticity. Indeed, during the fifteenth century, the idea of cultural inheritance between England and Wales was being more explicitly acknowledged, especially as Henry VII had used his descent from Cadwallader, the last king of the Britons, to legitimate his claim to the throne. According to Leland, then, the Historia still had political currency, and he consistently emphasises the authority of Geoffrey, the ‘good author’, in order to expose Vergil, the ‘foreigner’, as the unreliable fraud.

In De uiris Illustribus, Leland also includes an assessment of Vergil’s sources that he used in the Anglica Historia. Vergil’s account of early insular history relied heavily on Tacitus’ Agricola (c. 98) and Julius Caesar’s Commentarii de Bello Gallico (c. 58-49 BCE), both of which had grown in popularity during the Early Modern period. For Vergil, these Latin Caesar and Tacitus were more authoritative than Gildas and Bede, who lived several centuries later than the period they were writing about. Leland, however, remarks that

none of them [the Romans], as far as I know, wrote anything worth mentioning before Caesar. Besides, not everything that Caesar wrote – however much the Dunce [Polydore Vergil] makes of his statements – seems to me to have proceeded from an oracle; the same applies to many other things about the Britons which were later handed down to posterity by Latin authors. (Leland, pp. 310-13)

This assessment of Caesar is also a judgment of Polydore Vergil. Leland implies that it was unreasonable for Vergil to use Roman – and therefore biased – history in order to counteract Geoffrey’s version of ‘British’ history. Moreover, Leland also disregards the authority of Gildas and Bede, especially since the authorship of De Excidio Britanniae was subject to question after its publication in 1525, and the Historia Ecclesiastica included very little information on early ‘British’ history prior to the Saxon conquest. Leland’s detailed evaluation of his these sources interrogates the comparative methodology that Geoffrey’s critics used to disprove his account of insular history, and through his scholarly inquiry, Leland demonstrates that the Historia is the only real authority worth following.

The short biography of Geoffrey of Monmouth in De uirius Illustribus canonised the ‘British’ historian as an auctor – a term that, as A. J. Minnis points out, ‘denoted someone who was at once a writer and an authority, someone not merely to be read but also to be respected and believed’.[6] John Leland’s appraisal of Geoffrey challenged and disproved the objections of the critics of the Historia regum Britanniae, and his work later influenced the Welsh historians John Prise and Humphrey Llwyd, who both wrote defenses of Geoffrey in the latter half of the sixteenth century. These classically educated scholars and intellectuals held the Historia regum Britanniae in great esteem, rescuing its reputation from the likes of William of Newburgh and Polydore Vergil. Through their arguments, Leland, Prise, and Llwyd proved that Geoffrey’s authority and the veracity of his Historia was beyond all doubt.

This is a revised version of a paper given at the International Medieval Congress, University of Leeds (July 2015)

[1] This debate has been previously explored by James P. Carley, who viewed the antagonism between the two historians as prefiguring twentieth-century scholarship on the ‘historical Arthur’ that became increasingly popular among historians and archaeologists following the work of E. K Chambers and Leslie Alcock; see James P. Carley, ‘Polydore Vergil and John Leland on King Arthur: The Battle of the Books’, in King Arthur: A Casebook, ed. Edward Donald Kennedy (New York: Garland, 1996), pp. 185-204.

[2] Polydore Vergil’s English History, from an early translation presented among the MSS. of The Royal Library in the British Museum. Volume 1. Containing the First Eight Books, comprising the period prior to the Norman Conquest, ed. Sir Henry Ellis (London: Printed for the Camden Society, by John Bowyer Nichols and Son, Parliament Street, MDCCCXLVI), p. 29. All further references to Vergil’s Anglia Historia are to this edition and are given parenthetically in the text.

[3] William of Newburgh, The History of English Affairs, ed. and trans. P. G. Walsh and M. J. Kennedy (Warminster: Aris & Phillips, 1988), p. 29. All further references to William’s Historia rerum Anglicarum are to this edition and are given in the text.

[4] On the definitions of the auctor, scriptor, commentator, and compiler, see A. J. Minnis, Medieval Theory of Authorship: Scholastic Literary Attitudes in the Later Middle Ages (London: Scolar Press, 1984), p. 94.

[5] John Leland, De uiris Illustribus, ed. and trans. James P. Carley (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies and Oxford: Bodleian Library, 2010), p. 321. All further reference to Leland’s De uiris Illustribus are to this edition and are given parenthetically in the text. It should be noted that Leland’s length discussion on Polydore Vergil and King Arthur were later insertions, and the entry on Geoffrey of Monmouth in the first version of De uirius Illustribus was purely concerned with the writer in question.

[6] A. J. Minnis, The Medieval Theory of Authorship, p. 10.